Principles of Risk Management and Insurance 11th Edition Answers

Risk management is the process of identifying, assessing and controlling threats to an organization's capital and earnings. These risks stem from a variety of sources including financial uncertainties, legal liabilities, technology issues, strategic management errors, accidents and natural disasters.

A successful risk management program helps an organization consider the full range of risks it faces. Risk management also examines the relationship between risks and the cascading impact they could have on an organization's strategic goals.

This holistic approach to managing risk is sometimes described as enterprise risk management because of its emphasis on anticipating and understanding risk across an organization. In addition to a focus on internal and external threats, enterprise risk management (ERM) emphasizes the importance of managing positive risk. Positive risks are opportunities that could increase business value or, conversely, damage an organization if not taken. Indeed, the aim of any risk management program is not to eliminate all risk but to preserve and add to enterprise value by making smart risk decisions.

"We don't manage risks so we can have no risk. We manage risks so we know which risks are worth taking, which ones will get us to our goal, which ones have enough of a payout to even take them," said Forrester Research senior analyst Alla Valente, a specialist in governance, risk and compliance.

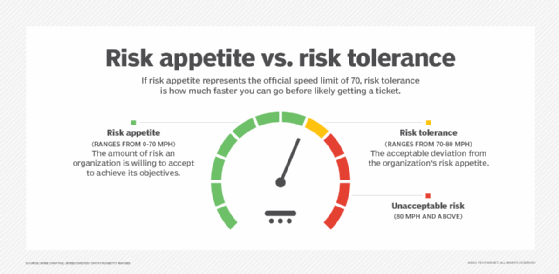

Thus, a risk management program should be intertwined with organizational strategy. To link them, risk management leaders must first define the organization's risk appetite -- i.e., the amount of risk it is willing to accept to realize its objectives.

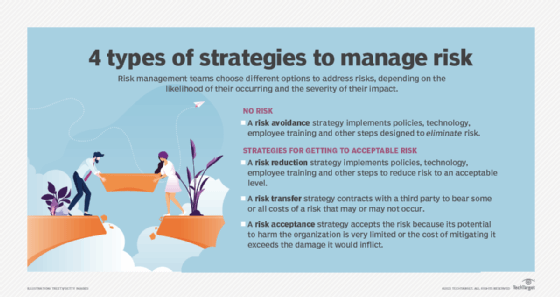

The formidable task is to then determine "which risks fit within the organization's risk appetite and which require additional controls and actions before they are acceptable," explained Notre Dame University Senior Director of IT Mike Chapple in his article on risk appetite vs. risk tolerance. Some risks will be accepted with no further action necessary. Others will be mitigated, shared with or transferred to another party, or avoided altogether.

Every organization faces the risk of unexpected, harmful events that can cost it money or cause it to close. Risks untaken can also spell trouble, as the companies disrupted by born-digital powerhouses, such as Amazon and Netflix, will attest. This guide to risk management provides a comprehensive overview of the key concepts, requirements, tools, trends and debates driving this dynamic field. Throughout, hyperlinks connect to other TechTarget articles that deliver in-depth information on the topics covered here, so readers should be sure to click on them to learn more.

Why is risk management important?

Risk management has perhaps never been more important than it is now. The risks modern organizations face have grown more complex, fueled by the rapid pace of globalization. New risks are constantly emerging, often related to and generated by the now-pervasive use of digital technology. Climate change has been dubbed a "threat multiplier" by risk experts.

A recent external risk that manifested itself as a supply chain issue at many companies -- the coronavirus pandemic -- quickly evolved into an existential threat, affecting the health and safety of their employees, the means of doing business, the ability to interact with customers and corporate reputations.

Businesses made rapid adjustments to the threats posed by the pandemic. But, going forward they are grappling with novel risks, including how or whether to bring employees back to the office and what should be done to make their supply chains less vulnerable to crises.

As the world continues to reckon with COVID-19, companies and their boards of directors are taking a fresh look at their risk management programs. They are reassessing their risk exposure and examining risk processes. They are reconsidering who should be involved in risk management. Companies that currently take a reactive approach to risk management -- guarding against past risks and changing practices after a new risk causes harm -- are considering the competitive advantages of a more proactive approach. There is heightened interest in supporting sustainability, resiliency and enterprise agility. Companies are also exploring how artificial intelligence technologies and sophisticated governance, risk and compliance (GRC) platforms can improve risk management.

Financial vs. nonfinancial industries. In discussions of risk management, many experts note that at companies that are heavily regulated and whose business is risk, managing risk is a formal function.

Banks and insurance companies, for example, have long had large risk departments typically headed by a chief risk officer (CRO), a title still relatively uncommon outside of the financial industry. Moreover, the risks that financial services companies face tend to be rooted in numbers and therefore can be quantified and effectively analyzed using known technology and mature methods. Risk scenarios in finance companies can be modeled with some precision.

For other industries, risk tends to be more qualitative and therefore harder to manage, increasing the need for a deliberate, thorough and consistent approach to risk management, said Gartner analyst Matt Shinkman, who leads the firm's enterprise risk management and audit practices. "Enterprise risk management programs aim to help these companies be as smart as they can be about managing risk."

Traditional risk management vs. enterprise risk management

Traditional risk management tends to get a bad rap these days compared to enterprise risk management. Both approaches aim to mitigate risks that could harm organizations. Both buy insurance to protect against a range of risks -- from losses due to fire and theft to cyber liability. Both adhere to guidance provided by the major standards bodies. But traditional risk management, experts argue, lacks the mindset and mechanisms required to understand risk as an integral part of enterprise strategy and performance.

For many companies, "risk is a dirty four-letter word -- and that's unfortunate," said Forrester's Valente. "In ERM, risk is looked at as a strategic enabler versus the cost of doing business."

"Siloed" vs. holistic is one of the big distinctions between the two approaches, according to Gartner's Shinkman. In traditional risk management programs, for example, risk has typically been the job of the business leaders in charge of the units where the risk resides. For example, the CIO or CTO is responsible for IT risk, the CFO is responsible for financial risk, the COO for operational risk, etc. The business units might have sophisticated systems in place to manage their various types of risks, Shinkman explained, but the company can still run into trouble by failing to see the relationships among risks or their cumulative impact on operations. Traditional risk management also tends to be reactive rather than proactive.

"The pandemic is a great example of a risk issue that is very easy to ignore if you don't take a holistic, long-term strategic view of the kinds of risks that could hurt you as a company," Shinkman said. "A lot of companies will look back and say, 'You know, we should have known about this, or at least thought about the financial implications of something like this before it happened.'"

In enterprise risk management, managing risk is a collaborative, cross-functional and big-picture effort. An ERM team, which could be as small as five people, works with the business unit leaders and staff to debrief them, help them use the right tools to think through the risks, collate that information and present it to the organization's executive leadership and board. Having credibility with executives across the enterprise is a must for risk leaders of this ilk, Shinkman said.

These types of experts increasingly come from a consulting background or have a "consulting mindset," he said, and possess a deep understanding of the mechanics of business. Unlike in traditional risk management, where the head of risk typically reports to the CFO, the heads of enterprise risk management teams -- whether they hold the chief risk officer title or some other title -- report to their CEOs, an acknowledgement that risk is part and parcel of business strategy.

In defining the chief risk officer role, Forrester Research makes a distinction between the "transactional CROs" typically found in traditional risk management programs and the "transformational CROs" who take an ERM approach. The former work at companies that see risk as a cost center and risk management as an insurance policy, according to Forrester. Transformational CROs, in the Forrester lexicon, are "customer-obsessed," Valente said. They focus on their companies' brand reputations, understand the horizontal nature of risk and define ERM as the "proper amount of risk needed to grow."

Risk averse is another trait of traditional risk management organizations. But as Valente noted, companies that define themselves as risk averse with a low risk appetite are sometimes off the mark in their risk assessment.

"A lot of organizations think they have a low risk appetite, but do they have plans to grow? Are they launching new products? Is innovation important? All of these are growth strategies and not without risk," Valente said.

To learn about other ways in which the two approaches diverge, check out technology writer Lisa Morgan's "Traditional risk management vs. enterprise risk management: How do they differ?" In addition, her article on risk management teams provides a detailed rundown of roles and responsibilities.

Risk management process

The risk management discipline has published many bodies of knowledge that document what organizations must do to manage risk. One of the best-known sources is the ISO 31000 standard, Risk Management -- Guidelines, developed by the International Organization for Standardization, a standards body commonly known as ISO.

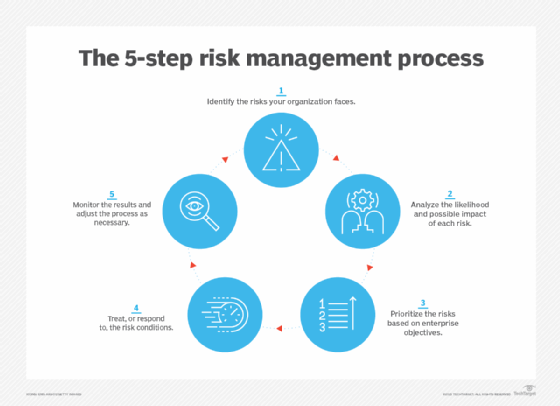

ISO's five-step risk management process comprises the following and can be used by any type of entity:

- Identify the risks.

- Analyze the likelihood and impact of each one.

- Prioritize risks based on business objectives.

- Treat (or respond to) the risk conditions.

- Monitor results and adjust as necessary.

The steps are straightforward, but risk management committees should not underestimate the work required to complete the process. For starters, it requires a solid understanding of what makes the organization tick. The end goal is to develop the set of processes for identifying the risks the organization faces, the likelihood and impact of these various risks, how each relates to the maximum risk the organization is willing to accept, and what actions should be taken to preserve and enhance organizational value.

"To consider what could go wrong, one needs to begin with what must go right," said risk expert Greg Witte, a senior security engineer for Huntington Ingalls Industries and an architect of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) frameworks on cybersecurity, privacy and workforce risks, among others.

When identifying risks, it is important to understand that, by definition, something is only a risk if it has impact, Witte said. For example, the following four factors must be present for a negative risk scenario, according to guidance from the NIST Interagency Report (NISTIR 8286A) on identifying cybersecurity risk in ERM:

- a valuable asset or resources that could be impacted;

- a source of threatening action that would act against that asset;

- a preexisting condition or vulnerability that enables that threat source to act; and

- some harmful impact that occurs from the threat source exploiting that vulnerability.

While the NIST criteria pertains to negative risks, similar processes can be applied to managing positive risks.

Top-down, bottom-up. In identifying risk scenarios that could impede or enhance an organization's objectives, many risk committees find it useful to take a top-down, bottom-up approach, Witte said. In the top-down exercise, leadership identifies the organization's mission-critical processes and works with internal and external stakeholders to determine the conditions that could impede them. The bottom-up perspective starts with the threat sources (earthquakes, economic downturns, cyber attacks, etc.) and considers their potential impact on critical assets.

Risk by categories . Organizing risks by categories can also be helpful in getting a handle on risk. The guidance cited by Witte from the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) uses the following four categories:

- strategic risk (e.g., reputation, customer relations, technical innovations);

- financial and reporting risk (e.g., market, tax, credit);

- compliance and governance risk (e.g., ethics, regulatory, international trade, privacy); and

- operational risk (e.g., IT security and privacy, supply chain, labor issues, natural disasters).

Another way for businesses to categorize risks, according to compliance expert Paul Kirvan, is to bucket them under the following four basic risk types for businesses: people risks, facility risks, process risks and technology risks.

The final task in the risk identification step is for organizations to record their findings in a risk register. It helps track the risks through the subsequent four steps of the risk management process. An example of such a risk register can be found in the NISTIR 8286A report cited above.

Witte provides an in-depth analysis of the entire process in his article, "Risk management process: What are the 5 steps?"

Risk management standards and frameworks

As government and industry compliance rules have expanded over the past two decades, regulatory and board-level scrutiny of corporate risk management practices have also increased, making risk analysis, internal audits, risk assessments and other features of risk management a major component of business strategy. How can an organization put this all together?

The rigorously developed -- and evolving -- frameworks developed by the risk management field will help.

Here is a sampling, starting with brief descriptions of the two most widely recognized frameworks. For more detail on them, readers should consult security expert Michael Cobb's analysis of ISO 31000 vs. COSO, which delves into their similarities and differences and how to choose between the two:

- COSO ERM Framework . Launched in 2004, the COSO framework was updated in 2017 to address increasing complexity of ERM. It defines key concepts and principles of ERM, suggests a common ERM language and provides clear direction for managing risk. Developed with input from COSO's five member organizations and external advisors, the framework is a set of 20 principles organized into five interrelated components:

- governance and culture

- strategy and objective-setting

- performance

- review and revision

- information, communication and reporting

As Cobb notes in his comparison article, COSO's updated version highlights the importance of embedding risk into business strategies and linking risk and operational performance.

- ISO 31000. Released in 2009 and revised in 2018, the ISO standard includes a list of ERM principles, a framework to help organizations apply risk management mechanisms to operations, and a process for identifying, evaluating, prioritizing and mitigating risk. The newer ISO version is a "shorter, clearer and more concise document that is easier to read" than its predecessor, according to Cobb. Developed by ISO's risk management technical committee with input from ISO national member bodies, the 2018 standard includes more strategic guidance on ERM than the original. The new standard also emphasizes the important role of senior management in risk management and the integration of risk management throughout the organization.

- British Standard (BS) 31100. The current version of this risk management code of practice was issued in 2011, and it provides a process for implementing concepts described in ISO 31000 -- including functions like identify, assess, respond, report and review.

- The Risk and Insurance Management Society's Risk Maturity Model (RMM). The RMM framework is currently undergoing an update, but it is readily available in the original 2006 version. RMM lists seven attributes of a risk management program and helps organizations assess each one on a scale from nonexistent to leadership level.

Enterprises might also consider establishing frameworks for specific categories of risks. Carnegie Mellon University's enterprise risk management framework, for example, examines potential risks and opportunities based upon the following risk categories: reputation, life/health safety, financial, mission, operational and compliance/legal.

What are the benefits and challenges of risk management?

Effectively managing risks that could have a negative or positive impact on capital and earnings brings many benefits. It also presents challenges, even for companies with mature governance, risk and compliance strategies.

Benefits of risk management include the following:

- increased awareness of risk across the organization;

- more confidence in organizational objectives and goals because risk is factored into strategy;

- better and more efficient compliance with regulatory and internal compliance mandates because compliance is coordinated;

- improved operational efficiency through more consistent application of risk processes and control;

- improved workplace safety and security for employees and customers; and

- a competitive differentiator in the marketplace.

The following are some of the challenges risk management teams should expect to encounter:

- Expenditures go up initially, as risk management programs can require expensive software and services.

- The increased emphasis on governance also requires business units to invest time and money to comply.

- Reaching consensus on the severity of risk and how to treat it can be a difficult and contentious exercise and sometimes lead to risk analysis paralysis.

- Demonstrating the value of risk management to executives without being able to give them hard numbers is difficult.

How to build and implement a risk management plan

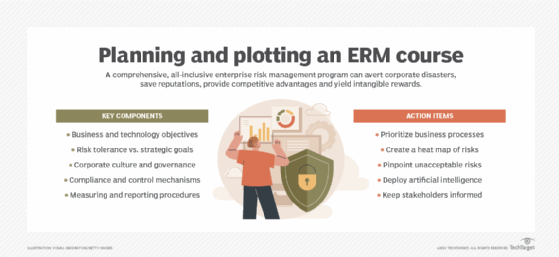

A risk management plan describes how an organization will manage risk. It lays out elements such as the organization's risk approach, roles and responsibilities of the risk management teams, resources it will use to manage risk, policies and procedures.

ISO 31000's seven-step process is a useful guide to follow, according to Witte. Here is a rundown of its components:

- Communication and consultation. Since raising risk awareness is an essential part of risk management, risk leaders must also develop a communication plan to convey the organization's risk policies and procedures to employees and relevant parties. This step sets the tone for risk decisions at every level. The audience includes anyone who has an interest in how the organization takes advantage of positive risks and minimizes negative risk.

- Establishing the context. This step requires defining the organization's unique risk appetite and risk tolerance -- i.e., the amount to which risk can vary from risk appetite. Factors to consider here include business objectives, company culture, regulatory legislation, political environment, etc.

- Risk identification. This step defines the risk scenarios that could have a positive or negative impact on the organization's ability to conduct business. As noted above, the resulting list should be recorded in a risk register and kept up to date.

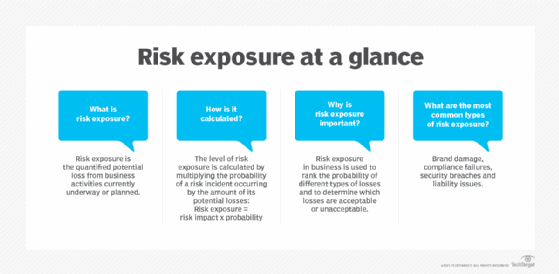

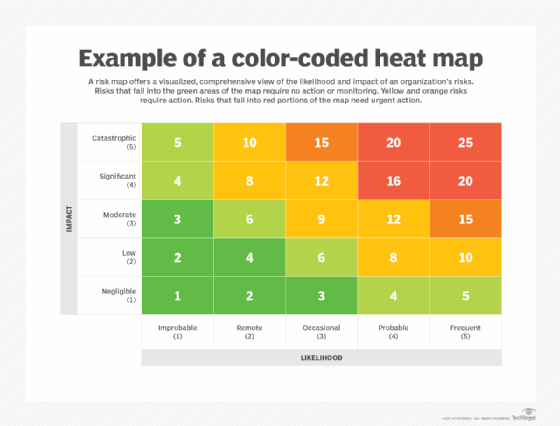

- Risk analysis. The likelihood and impact of each risk is analyzed to help sort risks. Making a risk heat map can be useful here, as it provides a visual representation of the nature and impact of a company's risks. An employee calling in sick, for example, is a high-probability event that has little or no impact on most companies. An earthquake, depending on location, is an example of a low-probability risk with high impact. The qualitative approach many organizations use to rate the likelihood and impact of risks might benefit from a more quantitative analysis, Witte said. The FAIR Institute, a professional association that promotes the Factor Analysis of Information Risk framework on cybersecurity risks, has examples of the latter approach.

- Risk evaluation. Here is where organizations determine how to respond to the risks they face. Techniques include one or more of the following:

- Risk avoidance: The organization seeks to eliminate, withdraw from or not be involved in the potential risk.

- Risk mitigation: The organization takes actions to limit or optimize a risk.

- Risk sharing or transfer: The organization contracts with a third party (e.g., an insurer) to bear some or all costs of a risk that may or may not occur.

- Risk acceptance: A risk falls within the organization's risk appetite and tolerance and is accepted without taking action.

- Risk treatment. This step involves applying the agreed-upon controls and processes and confirming they work as planned.

- Monitoring and review. Are the controls working as intended? Can they be improved? Monitoring activities should measure key performance indicators (KPIs) and look for key risk indicators (KRIs) that might trigger a change in strategy.

For more detail on what each step entails, consult Witte's article on ERM frameworks and their implementation in the enterprise.

Risk management best practices

A good starting point for any organization that aspires to follow risk management best practices is ISO 31000's 11 principles of risk management. According to ISO, a risk management program should meet the following objectives:

- create value for the organization;

- be an integral part of the overall organizational process;

- factor into the company's overall decision-making process;

- explicitly address any uncertainty;

- be systematic and structured;

- be based on the best available information;

- be tailored to the project;

- take into account human factors, including potential errors;

- be transparent and all-inclusive;

- be adaptable to change; and

- be continuously monitored and improved upon.

Another best practice for the modern enterprise risk management program is to "digitally reform," said security consultant Dave Shackleford. This entails using AI and other advanced technologies to automate inefficient and ineffective manual processes.

Risk management limitations and examples of failures

Risk management failures are often chalked up to willful misconduct, gross recklessness or a series of unfortunate events no one could have predicted. But, as technology journalist George Lawton pointed out in his examination of common risk management failures, risk management gone wrong is more often due to avoidable missteps -- and run-of-the-mill profit-chasing. Here is a rundown of mistakes to avoid.

Poor governance . The 2020 tangled tale of Citigroup accidentally paying off a $900 million loan, using its own money, to Revlon's lenders when only a small interest payment was due shows how even the largest bank in the world can mess up risk management -- despite having updated policies for pandemic work conditions and multiple controls in place. Human error and clunky software were involved, but ultimately a judge ruled poor governance was the root cause. Citigroup was fined $400 million by U.S. regulators and agreed to overhaul its internal risk management, data governance and compliance controls.

Overemphasis on efficiency vs. resiliency. Greater efficiency can lead to bigger profits when all goes well. Doing things quicker, faster and cheaper by doing them the same way every time, however, can result in a lack of resiliency, as companies found out during the pandemic when supply chains broke down. "When we look at the nature of the world … things change all the time," said Forrester's Valente. "So, we have to understand that efficiency is great, but we also have to plan for all of the what-ifs."

Lack of transparency. The scandal involving the misrepresentation of coronavirus-related deaths at New York nursing homes by the governor's office is representative of a common failing in risk management. Hiding data, lack of data and siloed data -- whether due to acts of commission or omission -- can cause transparency issues. As risk expert Josh Tessaro told Lawton, "Many processes and systems were not designed with risk in mind." Data is disconnected and owned by different leaders. "Risk managers often then settle for the data they have that is easily accessible, ignoring critical processes because the data is hard to get," Tessaro said.

Limitations of risk analysis techniques. Many risk analysis techniques, such as creating a risk model or simulation, require gathering large amounts of data. Extensive data collection can be expensive and is not guaranteed to be reliable. Furthermore, the use of data in decision-making processes may have poor outcomes if simple indicators are used to reflect complex risk situations. In addition, applying a decision intended for one small aspect of a project to the whole project can lead to inaccurate results.

Lack of risk analysis expertise . Software programs developed to simulate events that might negatively impact a company can be cost-effective, but they also require highly trained personnel to accurately understand the generated results.

Illusion of control. Risk models can give organizations the false belief that they can quantify and regulate every potential risk. This may cause an organization to neglect the possibility of novel or unexpected risks.

Risk management trends: What's on the horizon?

The spotlight shined on risk management during the COVID-19 pandemic has driven many companies to not only reexamine their risk practices but also to explore new techniques, technologies and processes for managing risk. As Lawton's reporting on the trends that are reshaping risk management shows, the field is brimming with ideas.

More organizations are adopting a risk maturity framework to evaluate their risk processes and better manage the interconnectedness of threats across the enterprise. They are looking anew at GRC platforms to integrate their risk management activities, manage policies, conduct risk assessments, identify gaps in regulatory compliance and automate internal audits, among other tasks. New GRC features under consideration include the following:

- analytics for geopolitical risks, natural disasters and other events;

- social media monitoring to track changes in brand reputation; and

- security systems to assess the potential impact of breaches and cyber attacks.

In addition to using risk management to avoid bad situations, more companies are looking to formalize how to manage positive risks to add business value.

They are also taking a fresh look at risk appetite statements. Traditionally used as a means to communicate with employees, investors and regulators, risk appetite statements are starting to be used more dynamically, replacing "check the box" compliance exercises with a more nuanced approach to risk scenarios. The caveat? A poorly worded risk appetite statement could hem in a company or be misinterpreted by regulators as condoning unacceptable risks.

Finally, while it's tough to make predictions -- especially about the future, as the adage goes -- tools for measuring and mitigating risks are getting better. Among the improvements? Internal and external sensing tools that detect trending and emerging risks.

This was last updated in October 2021

Principles of Risk Management and Insurance 11th Edition Answers

Source: https://searchcompliance.techtarget.com/definition/risk-management